A TRIUMPH OF ADVOCACY

The wrecking ball does not seem to respect boundaries and the sacrosanct character of certain structures, like the official residence of the Philippine Ambassador in Tokyo, Japan. This edifice is considered an extension of Philippine territory by virtue of the principle of extraterritoriality in international law. Known as the Fujimi property because of its location, the residence has long been the much-coveted apple in the eyes of so-called “developers”. It was the subject of numerous attempts at privatization oblivious of its provenance, historical pedigree and diplomatic value to the Philippines.

The wrecking ball does not seem to respect boundaries and the sacrosanct character of certain structures, like the official residence of the Philippine Ambassador in Tokyo, Japan. This edifice is considered an extension of Philippine territory by virtue of the principle of extraterritoriality in international law. Known as the Fujimi property because of its location, the residence has long been the much-coveted apple in the eyes of so-called “developers”. It was the subject of numerous attempts at privatization oblivious of its provenance, historical pedigree and diplomatic value to the Philippines.

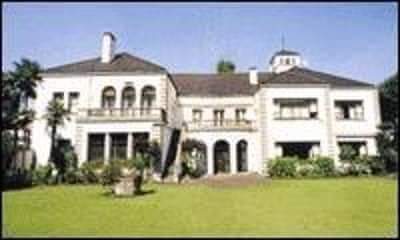

Measuring 5,219 square meters and situated near the Imperial Palace of the Emperor, the Fujimi property has a structure of Iberian magnificence. It is the most beautiful Philippine Ambassador’s residence in the world. The Philippine Historical Committee, precursor of the National Historical Institute installed on March 9, 1952 a historical marker which stated: “This property, dating from the Tokugawa Shogunate, was purchased for the Philippines on 31 March 1944 by President Jose P. Laurel of the Second Philippine Republic.” (In the last attempt to privatize the Fujimi property in 2009, the Bids and Awards Committee-Japan (BAC-Japan) tried to downgrade the importance of the marker by claiming without any proof that the property was part of the Japanese reparation payments to the Philippines after Second World War.)

Measuring 5,219 square meters and situated near the Imperial Palace of the Emperor, the Fujimi property has a structure of Iberian magnificence. It is the most beautiful Philippine Ambassador’s residence in the world. The Philippine Historical Committee, precursor of the National Historical Institute installed on March 9, 1952 a historical marker which stated: “This property, dating from the Tokugawa Shogunate, was purchased for the Philippines on 31 March 1944 by President Jose P. Laurel of the Second Philippine Republic.” (In the last attempt to privatize the Fujimi property in 2009, the Bids and Awards Committee-Japan (BAC-Japan) tried to downgrade the importance of the marker by claiming without any proof that the property was part of the Japanese reparation payments to the Philippines after Second World War.)

The long and arduous road to preservation

In its 10 March 2014 issue, the Philippine Star heralded the good news that Ambassador to Japan Manuel Lopez and National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) Chair Maria Serena Diokno had unveiled an NHCP marker at the Fujimi property proclaiming the Ambassador’s official residence as a “National Historical Landmark” pursuant to Resolution No.01 adopted by the NHCP on 11 March 2013.

The NHCP has defined a National Historical Landmark as a “site or structure closely associated with a historical event, achievement, characteristic turning point or stage in Philippine history.” Thus, Kudan, the popular reference to the Ambassador’s residence, became the first national historical landmark outside of the Philippines. The NHCP resolution “urged the national government to retain, protect and preserve the site as part of the national patrimony.”

The momentous occasion in Tokyo could not have taken place if the Philippine Ambassadors Foundation Inc. (PAFI) did not come into the picture. It was PAFI’s earnest efforts, determination and perseverance that made possible the installation of the marker.

PAFI was originally founded as the Philippine Ambassadors Association on 19 January 1978 by distinguished diplomats, including Ambassadors Salvador P. Lopez and Jose S. Laurel III. After celebrating the 30th anniversary of its founding on 28 February 2008 at the RCBC Plaza, PAFI acquired new vigor, sense of purpose and commitment under the leadership of Ambassador Alfonso T. Yuchengco as Chairman and Ambassador Jose Macario Laurel IV as President. The organization sought to address issues that impinge not only on our foreign relations but also on our nationhood. A common view emerged, i.e., that retirement does not mean that former diplomats have ceased to be stakeholders in their country’s present and future.

PAFI was originally founded as the Philippine Ambassadors Association on 19 January 1978 by distinguished diplomats, including Ambassadors Salvador P. Lopez and Jose S. Laurel III. After celebrating the 30th anniversary of its founding on 28 February 2008 at the RCBC Plaza, PAFI acquired new vigor, sense of purpose and commitment under the leadership of Ambassador Alfonso T. Yuchengco as Chairman and Ambassador Jose Macario Laurel IV as President. The organization sought to address issues that impinge not only on our foreign relations but also on our nationhood. A common view emerged, i.e., that retirement does not mean that former diplomats have ceased to be stakeholders in their country’s present and future.

At the PAFI board meetings, Amb. Abaquin presented two papers one of which contained a copy of the letter of Mr. Francis C. Laurel, President of the Philippines-Japan Society Inc. For his part Amb. Laurel circulated a copy of the letter of former Secretary of Foreign Affairs and then Ambassador to Japan Domingo L. Siazon, Jr. The two letters were related to the public bidding to be conducted by the Arroyo Administration for the lease and development of the Fujimi property. Mr. Laurel was asking the then National Historical Institute (NHI) whether the marker installed at the Fujimi property had conferred on it landmark or historic status and, thus under the protection of the NHI. In his letter addressed to then Foreign Secretary Alberto G. Romulo, Amb. Siazon emphasized the importance of the property and expressed support for its preservation. His wife, Kazuko Siazon, produced with the help of the Embassy staff an illustrated book on the Kudan, tracing its history and showing its interior and outdoor premises.

At the PAFI board meetings, Amb. Abaquin presented two papers one of which contained a copy of the letter of Mr. Francis C. Laurel, President of the Philippines-Japan Society Inc. For his part Amb. Laurel circulated a copy of the letter of former Secretary of Foreign Affairs and then Ambassador to Japan Domingo L. Siazon, Jr. The two letters were related to the public bidding to be conducted by the Arroyo Administration for the lease and development of the Fujimi property. Mr. Laurel was asking the then National Historical Institute (NHI) whether the marker installed at the Fujimi property had conferred on it landmark or historic status and, thus under the protection of the NHI. In his letter addressed to then Foreign Secretary Alberto G. Romulo, Amb. Siazon emphasized the importance of the property and expressed support for its preservation. His wife, Kazuko Siazon, produced with the help of the Embassy staff an illustrated book on the Kudan, tracing its history and showing its interior and outdoor premises.

Upon learning that nine (9) Japanese companies had signified their interest to bid for the property under the a 50-year lease, Ambassadors Yuchengco and Laurel addressed a letter dated 10 June 2008 to President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. They appealed to the President’s fair sense of judgment and patriotism to prevent the destruction of the property that reflects the historic past and heritage of our country and people. They also pointed out that under the plan, the Ambassador’s residence would be demolished and replaced with a 21-storey structure, the penthouse of which would serve as the Ambassador’s residence. This would diminish the Ambassador’s representative character. It would also be an uncomfortable arrangement since questions concerning the availing of diplomatic immunity as well as the provision of security to the premises could arise since the lower floors would be occupied by private tenants and commercial entities.

Ambassadors Yuchengco and Laurel also sent a letter dated 22 September 2008 to NHI Chairman Ambeth R. Ocampo requesting the latter to register the Ambassador’s residence in Tokyo as a historic site.

Since no reply was forthcoming from the President, Ambassadors Yuchengo and Laurel, accompanied by Amb. Abaquin and Amb. Juanito P. Jarasa, Secretary General, called on Executive Secretary Eduardo R. Ermita in Malacanang regarding their letter. Mr. Ermita, in a letter dated 6 May 2009, informed the two ambassadors “that the proposed demolition of the Embassy residence has been set on hold by order of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. We are not expecting any demolition and/or alteration on said valuable piece of property that reflects the historic past and heritage of our country and people in the near future, specifically during the term of President Arroyo.”

Instead of being assured, the PAFI Board was alarmed by certain developments; BAC-Japan, which was in charge of the bidding for the Fujimi property, was going ahead with the bidding process, apparently unaware of or simply ignoring Ermita’s letter. It was reported that the Department of Finance, BAC-Japan chairman, had scheduled the announcement of the winning bidder on 2 December 2009. Meanwhile, the Department of Foreign Affairs, a member of BAC-Japan, appeared unapproachable. The Secretary of Foreign Affairs cancelled a scheduled meeting with the PAFI President.

The anxiety was somehow alleviated by the significant support manifested by NHI Chairman Ocampo. In his letter dated 29 October 2009 to Pres. Arroyo, Ocampo expressed support “for the call of PAFI to stop the planned auction of the Philippine Government’s Fujimi Property in Tokyo, Japan.” He also said:

“A historical marker was installed on the property by the Philippines Historical Committee, precursor of the National Historical Institute on March 9, 1952. It is considered a classified structure under the Registry of Historic Sites and Structures in the Philippines, being maintained by the NHI. With its category as such, it is a historical site, and therefore, we believe that it should be preserved as part of the country’s heritage and patrimony, as provided for in the Constitution.

We appeal to Her Excellency to act within the powers of her office and save what is considered as “the most beautiful Philippine Ambassador’s residence in the world” from destruction.”

Faced with ucertainty over the outcome of its advocacy, the PAFI Board decided that the best course of action was to elevate the matter to the Supreme Court. For this purpose, PAFI availed itself of the pro bono services of Atty.Catalino Aldea Generillo, Jr. He was a magna cum laude graduate of the Lyceum of the Philippines who gained prominence through the column of Solita Monsod of the Philippine Daily Inquirer. He served as special counsel of the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) from 2001 under the late Haydee Yorac.

Atty. Generillo studied thoroughly the Fujimi case before writing the Petition that earned the approval of the PAFI Board. The PAFI cause got a big political boost from then Senator Aquilino Q. Pimentel Jr. who joined the bandwagon through the intercession of PAFI Governor Jose Zaldarriaga.

On 1 December 2009, Ambassador Laurel, representing PAFI and himself, and Senate Minority Leader Pimentel personally filed with the Supreme Court a petition for the issuance of a Temporary Restraining Order directing the Bidding and Awards Committee-Japan (BAC-Japan) to refrain from accepting proposals for the right to develop and lease the property of the Philippine government in Fujimi, Tokyo, Japan. The petitioners were accompanied by PAFI counsel Atty. Generillo and Amb. Jarasa. Named as RESPONDENTS were Secretary of Finance Margarito F. Teves, Secretary of Foreign Affairs Alberto G. Romulo and representatives to BAC-Japan from the DOF, DFA, DBM, DPWH, DOJ and the office of the Executive Secretary.

The Respondents (BAC-Japan) immediately opposed the

Petitioners application for the issuance of a TRO principally on the basis of a letter-reply sent by NHI Chairman Ocampo to BAC-Japan Chairman and Secretary of Finance Margarito Teves, the pertinent portions of which state:

“The Fujimi property now the residence of the Philippine Ambassador to Japan was recognized and marked by the Philippine Historical Committee (PHC), now National Historical Institute on March 9, 1952, therefore it is listed in the registry of historic sites and structures in the Philippines.

“While the structure is not a declared National Historical Landmark and does not require our written permission for alteration, it remains a “classified” structure and we strongly recommend its preservation.

“However, we yield to your best judgment on the issue based on national interest.”

On 30 November 2010, the Supreme Court en banc adopted the following resolution:

“Acting on the Supplement (to all Pleadings Filed by the Petitioners), with prayer for a temporary restraining order, dated July 12, 2010, the Court resolved to REQUIRE the parties to observe the STATUS QUO prevailing before the public bidding for the right to lease and develop the Fujimi property in Tokyo, Japan.” Therefore, the SC blocked the lease of the Fujimi property.

Subsequently, the resourceful lawyer furnished the PAFI Board a copy of Republic Act No. 10066 or the National Cultural Heritage Act of 2009. The Act expanded Presidential Decree No. 1505 of 1978 by defining National Cultural Treasurers (NCTs) as those falling under the categories of Important Cultural Properties (ICPs), World Heritage Sites declared by UNESCO, National Historical Shrines and National Historical Landmarks. These NCTs are declared as such by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), the new name of the National Historical Institute.

Since the final decision of the Supreme Court on the Fujimi case was pending, the PAFI saw the Act as another avenue for protecting the property. In this regard, Ambassador Jarasa hosted a luncheon meeting to have exploratory and procedural consultation with Ludovico Badoy, Executive Director of the NHCP, and three other NHCP executives and Gemma Cruz-Araneta, President of Heritage Conservation Society. Ambassador Abaquin, who accompanied Ambassador Jarasa, related to the group the antecedents of the Fujimi case. In view of the encouraging result of the consultation, the PAFI Board instructed Ambassador Jarasa to craft the letter or petition to the NHCP.

In the three-page letter to the NHCP dated 31 March 2011 and signed by Ambassador Laurel, the Commission was informed of PAFI’s course of action and of outstanding features as well as importance of the Fujimi residence. The petition sought the declaration of the Fujimi property as an Important Cultural Property (ICP) and the placement of a Heritage Marker on the property. It was stated that the property was already a marked structure in view of the historical marker installed in it in 1952. It was also stressed that the petition was being filed in accordance with Section 8 of RA 10066 by PAFI as a “stakeholder” since it is a duly registered organization drawing its membership from active and retired ambassadors of the Philippine Foreign Service and that its present Chairman (Amb. Yuchengco) and PAFI Governor (Amb.Siazon) have both served as envoys to Japan and had lived in the Kudan during their tour of duty in Tokyo. Pictures and relevant documents accompanied the petition.

The petition was addressed to then Chairman Ocampo who was subsequently replaced by Dr. Maria Serena I. Diokno, daughter of the late Sen. Jose W. Diokno, as NHCP Chair.

When Amb. Laurel followed up the petition, Dr. Diokno replied by letter dated 24 May 2011 embodying the following paragraph:

“On 26 April 2011, the NHCP received a letter from the Office of the Solicitor General advising us to respect the Status Quo Ante Order issued by the Supreme Court on 30 November 2010, by refraining from being involved with the case until the Supreme Court has issued a decision. I regret, therefore, that the Commission is constrained from declaring the Fujimi property a historical landmark.”

However, Dr. Diokno called attention to Section 5 of RA 10066 which prescribes that all structures fifty (50) years old or older (like the Fujimi property) are important cultural properties, unless declared otherwise by the NHI. Then, she emphatically stated: “The Commission has not declared otherwise with regard to the nature of the Fujimi property as an important cultural property.”

Thereafter, Amb. Laurel and Dr. Diokno herself conducted their own networking and personal representation. It then came to PAFI’s attention that on 21 September 2012, BAC-Japan, through the Office of the Solicitor General, notified the Supreme Court:

“That they are no longer proceeding with the negotiated procurement of the Fujimi property, without prejudice to the future disposition of the property through other modes of procurement.”

On November 27, 2012, the Supreme Court en banc adopted a Resolution stating the “instant Petition praying for the nullification of the public bidding to lease and develop the Fujimi property has been rendered moot and academic.” The decision became final and executory on 8 January 2013. The NHCP Board meeting on 11 March 2013 declared the Fujimi property a National Historical Landmark.

The denouement of the Fujimi case can justifiably be classified as a triumph of advocacy. However, there are no iron-clad guarantees that the Fujimi property will remain preserved for posterity. The Supreme Court has refrained from “expressing its opinion in a case where no legal relief is needed or called for.” For as long as human beings are swayed by whims and caprices, nothing is assured.

Leave a Reply